Volume 1

How are students feeling about their learning and school? Data from Cognia’s Student Engagement Survey reveal actionable insights.

The data

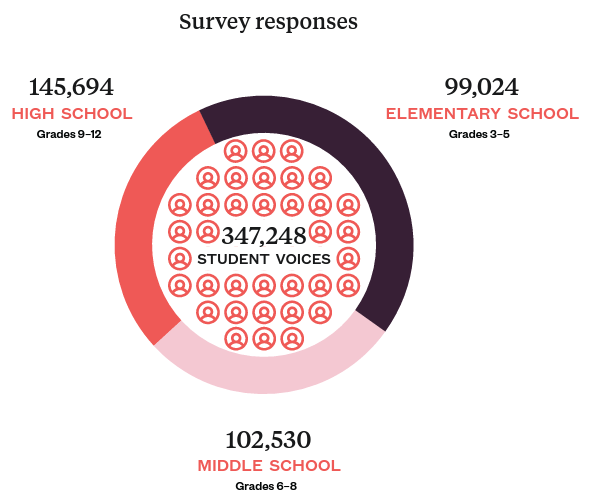

Between July 2020 and June 2021, 347,248 students from across the world shared their feelings about their engagement in school. The Cognia Student Engagement Survey (SES) was administered in 1,633 schools. U.S. students made up 94% of respondents; 6% of the students were enrolled in schools in the Middle East and Latin America.

The survey

First introduced in 2017, the SES provides students an opportunity to voice how they feel about their classroom and school experiences. School personnel can use the survey results to learn about, reflect on, and respond to what students say about their experiences.

Three Engagement Domains

Behavioral Domain—Students’ efforts in the classroom

Cognitive Domain—Students’ investment in learning

Emotional Domain—Students’ emotions or feelings about their classroom and school

Three Types of Engagement

Committed—Students find personal meaning and value in tasks

Compliant—Students strive to meet learning expectations, follow rules, and actively avoid consequences

Disengaged—Students are unmotivated, actively avoid completing tasks, and have low participation

Why this survey matters

Before March 2020, educators had the opportunities to listen to, learn from, and observe students in “real time” in their classes, giving them access to a plethora of information about students’ needs and interests. This realtime access allowed educators to adjust school schedules, extracurricular activities, and classroom learning experiences to improve student engagement. However, after March 2020 having access to student voices was inconsistent and difficult, which makes the results of these student engagement surveys essential for moving forward in today’s uncertain world of schooling. Students want educators to listen and respond to their voices, and in this context, to their perspectives about engaging in school and their classrooms.

What their voices tell us

Collectively, the 347,248 student voices revealed that:

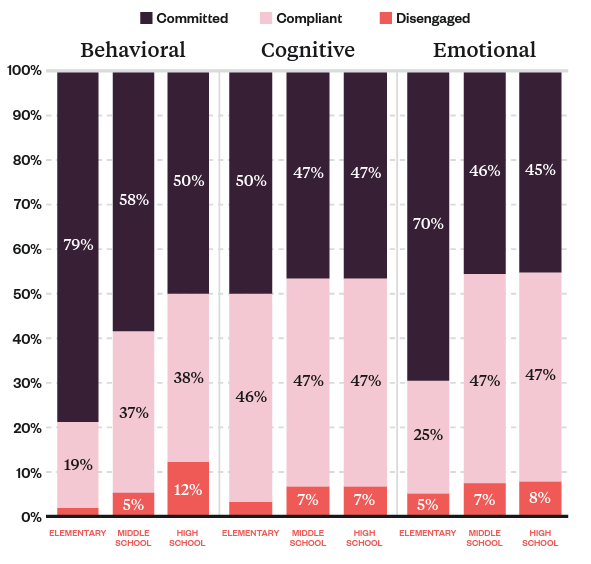

- Across all grade bands and domains, more than 88% of students indicated they were committed or compliant in their engagement with their learning or with their school.

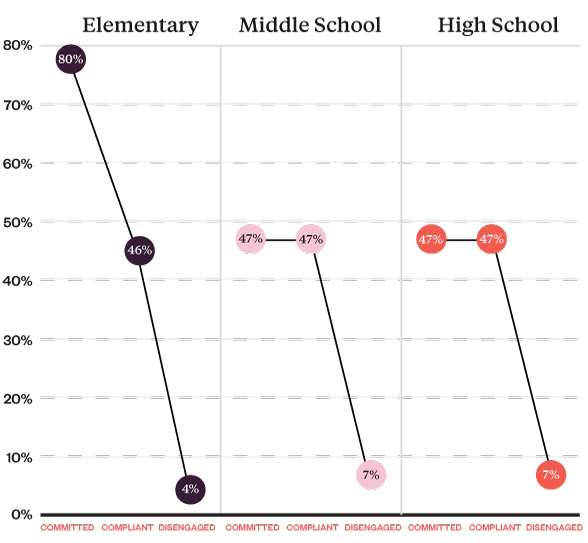

- Across all grade bands, about half of the students indicated cognitive commitment to their academic work and learning, such as taking initiative and finding ways to make the assignment relevant to their lives.

- About half of the students across all grade bands responded to items that indicated their cognitive compliant engagement, such as getting good grades or performing well on tests to please their teachers and families.

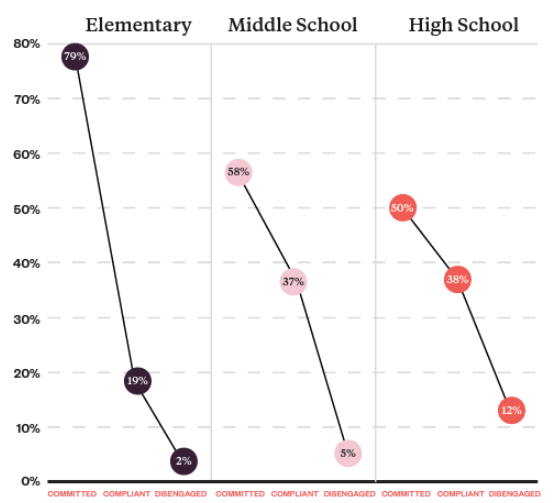

- Elementary student responses indicated higher levels of behavioral commitment when compared to older students in areas such as the effort they put forth to complete their work.

- Elementary students also indicated strong committed emotional engagement regarding their positive feelings about their school and classroom and taking ownership to stay positive when compared to middle and high school student responses.

-

About one-third of middle and high school students indicated compliant behavioral engagement, such as demonstrating certain behaviors to please their teachers and families and meet their expectations.

-

Middle and high school student responses were almost evenly distributed in the committed and compliant levels of the emotional domain, indicating that about half of the students were committed to generating their own connections to others and creating a sense of belonging.

Student Engagement by Domain and Grade, AY21

Engagement changes with grade-level bands

According to Goldstein, Boxer, & Randolph (2015), students’ level of engagement decreases during grade-level transitions, such as from elementary to middle and middle to high school. Student voices from the survey confirmed that adapting to a new school, grade structure, or expectations were among the variables that could decrease students’ level of engagement when they matriculate to middle school and high school. One possibility for the decline in engagement that middle and high school students experienced during the twelve-month period could be attributed to increased screen time for instruction. This is most salient in the behavioral domain, as illustrated by the 21% drop from elementary to middle school.

Behavioral engagement percentages

Engagement increases when students invest in learning

Cognitive engagement is directly linked to achievement and is a stronger predictor for learning than the other two engagement domains (Barlow, Brown, Lutz, et al., 2020; Pickering, 2017). Students who are invested in their own learning generally exceed expectations set by their teachers and families and meet new challenges as opportunities to make connections with existing knowledge. On the other hand, compliant students typically respond to extrinsic rewards, such as being recognized for completing their work or getting good grades but fall short of taking initiative to immerse themselves more deeply in the learning. It is reasonable that students felt more compliant during this survey period because they were more reliant on their parents, family members, and other people to monitor their learning and completion of assignments. Large percentages of compliant student responses in the cognitive domain were demonstrated in elementary (46%), middle (47%), and high school (47%).

Cognitive engagement percentages

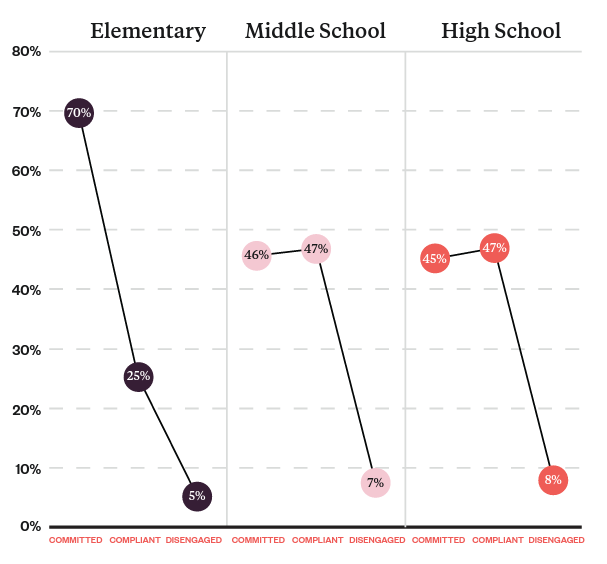

Engagement is enhanced through positive relationships

Research conducted as far back as 1997 (Birch & Ladd, 1997) indicates that students with positive teacher and peer relationships—meaning they feel connected—are generally more engaged in their learning activities. Emotional commitment was shown to be highest for elementary school students (70%) and notably lower for middle and high school students (46% and 45%). Older students shared that they felt less connected with people and that their opportunities to form relationships were challenging. Perhaps the decrease from committed to compliant engagement in the Emotional Domain could be attributed to the unusual circumstances related to COVID-19 when students had fewer group and collaborative learning activities that help develop relationships among students and teachers.

Emotional engagement levels by grade-level

What educators can do

The evidence-based strategies presented below can increase learners’ level of engagement in more than one domain and are appropriate for learners in grades 3–12. This is not an exhaustive list.

STRATEGY |

THE WHAT |

THE HOW |

| Think Differently | Students express and explain their opinions about a topic or questions while acknowledging that disagreement among their peers is healthy. |

Students respond to a statement made by the teacher or their peers by moving to designated areas in the classroom to indicate their stance: strongly agree, strongly disagree, or unsure. As students in each group explain their stance, they can change their minds by moving to a different area in the classroom. |

| Tiered Assignments | Students have opportunities to explore/ develop skills at different levels of complexity, abstractedness, and openendedness, rather than through tiered lesson/learning objectives. | Students choose activity tasks according to their level of readiness. Students with proficient skills may create a story web, while those with advanced skills participate in retelling a story from another viewpoint. |

| Pair-Shares | Students work with a partner using enhanced Think-Pair-Share practice (Lochhead Whimbey, 1987). | Students share their partner’s answer(s), rather than their own, to the whole group, and ask the partner to explain their answer well. |

| Think-Aloud Problem Solving |

Students work together in groups of three, with each having a specific role in solving a problem or engaging in a discussion around a topic. | Each student fulfills their assigned role, culminating in the explainer presenting the group’s results. The learners share their insights about the types of questions that were the most helpful and why. |

| Two-Voice Poems | Students use compare/contrast strategy to create a poem that demonstrates two different perspectives on a topic. | Students create a two-voice poem by writing comments as a back-and-forth conversation. Students use an organizer with three sections. In one section, they list all that is known about the topic. Then, they create comments that would be expressed about the topic in the other two sections. |

| Circle of Power and Respect (CPR) | Students practice and apply a format of greeting, sharing, activity, and daily news to develop leadership, autonomy, safety, inclusivity, and positive relationships. | Students gather as a whole group for 20 minutes each day to move from teacher-facilitated to learner-directed activities. The teacher models the practice and guides a pair of students through a process to design and lead. |

References

Association of Independent Schools New South Wales (n.d.). Engagement strategies: Pair-Share. https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/teachers-and-staff/teaching-and-learning/literacy-and-numeracy/foundations-of-effective-instruction/engagement-strategies/pair-share

Barlow, A., Brown, S., Lutz, B. Pitterson, N., Hunsu, N., & Adesope, O. (2020). Developing the student course cognitive engagement instrument (SCCEI) for college engineering courses. IJ STEM Ed, 7(22). https://stemeducationjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40594-020-00220-9

Birch, S.H., & Ladd, G.W. (1977). The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 61-80.

Blackburn, B. & Witzel, B. S. (2018). Rigor in the RTI and MTSS classroom: Practical tools and strategies. (1st ed.). Routledge.

EL Education (n.d.). Helping all learners: Tiering. https://eleducation.org/resources/helping-all-learners-tiering

Goldstein, S., Boxer, P., & Randolph, E. (2015). Middle school transition stress: Links with academic performance, motivation, and school experiences. Contemporary School Psychology, 2015 (19), 21-29.

Klug, E. (2011). Student-led circle of power and respect—The Origins Program.

Lochhead, J. & Whimbey, A. (1987). Teaching analytical reasoning through thinking aloud pair problem solving. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1987(30), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.37219873007

Pickering, J.D. (2017). Cognitive engagement: A more reliable proxy for learning? Medical Science Educator, 27, 821-823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-017-0447-8

Silver, H., Abla, C., Boutz, A., & Perini, M. (2018). Tools for classroom instruction that works. McRel International.